By Rev. Donald L. Perryman, Ph.D.

The Truth Contributor

Justice cannot be for one side alone but must be for both.

– Eleanor Roosevelt

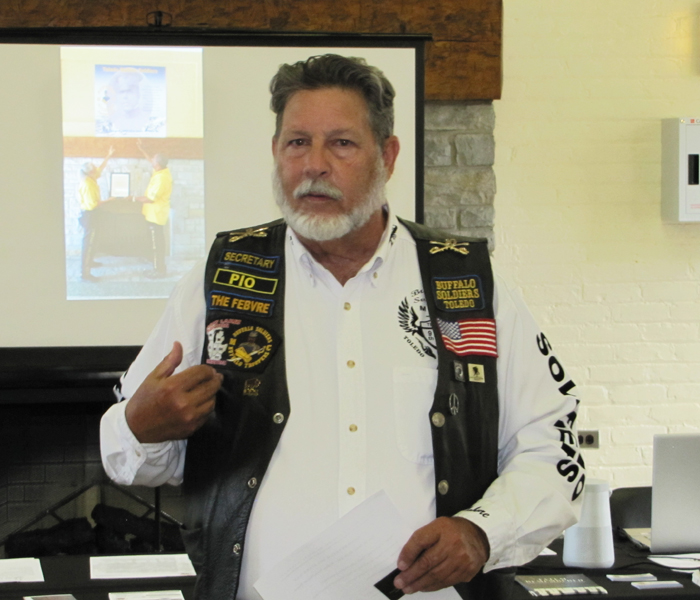

Fred LeFebvre is an enigma in today’s polarized political climate.

The host of the long-running “morning show,” LeFebvre is arguably the preeminent voice in Toledo’s media landscape and, for over 40 years, has been a part of WSPD, the dominant station in local conservative talk radio programming.

Yet, Fred defies the typical expectations given the nation’s widening ideological divide and deepening partisan hostility. A child of the Civil Rights Movement, his journey from growing up in the suburbs of Detroit to settling in Toledo, where he has been embedded in the community advocating for local initiatives, has shaped his uncommon worldview.

This intersection of Fred’s conservative roots with his passion for community-driven change has also produced a pragmatic approach often missing in today’s hyper-partisan environment, making him an enigmatic figure who resists being easily categorized simply as a binary “conservative” or “progressive.”

I caught up with Fred to discuss his enigmatic perspective. Hear the conversation in his own words.

Perryman: Let’s start by telling us a little bit about yourself. What brought you to Toledo?

LeFebvre: I started in radio about 46-47 years ago in Celina, Ohio. After a couple of years of working down there, I got a call from the management at what was then WMHE 92.5 on Bancroft Street, who promised to pay me more money than what I was making, and that was enough.

Perryman: How old were you when you came to Toledo?

LeFebvre: I was 29. I’m originally from Lincoln Park, Michigan, which is a suburb of Detroit. I went to high school in Detroit itself and actually lived in the city for a number of years. I worked in the city in the grocery industry before getting into radio and moving to Ohio.

Perryman: Please elaborate on your early formation.

LeFebvre: I was in high school from ’65 to ’69, so that was the best time for music. Those were the best years for rock and roll, Motown and all the changes happening. Everything was happening like the War in Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement through all those years.

I was old enough to remember the assassination of John Kennedy. I watched the funeral on T.V. and see Jack Ruby shooting Oswald in the basement of the Dallas Police Department, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King and Medgar Evers, and all of that stuff happened during my teenage years.

Perryman: Compare Toledo’s vibe or regional culture to Michigan. What makes you unique?

LeFebvre: I grew up in the suburbs, and no African Americans were in my neighborhood. We watched the Civil Rights Movement on T.V., but I don’t think my parents understood. Their attitude at the time was, “These people, what do they want?” Then they sent me to high school in the City of Detroit, and I was going to high school with African American kids whose parents were sending them to this Catholic school where there was a tuition that had to be paid, but those parents wanted their kids to have the same stuff that I had already. They also wanted their kids to have a better life and grew up in neighborhoods that were nothing like the neighborhoods where I grew up in Lincoln Park.

So, I went to high school with a pretty good melting pot and really learned there that we had a whole lot more in common than we had in differences.

Perryman: How did you first become engaged with Toledo’s African American community groups?

LeFebvre: I first saw Earl Mack speak at my daughter’s high school, Notre Dame, about the responsibility parents have for making sure graduation parties and other events don’t get out of hand, and I thought, man, this guy has a lot to say.

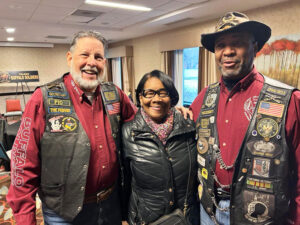

Then, about 10 years later, I heard about his involvement with the Buffalo Soldiers and invited him on air because I’ve always believed we can’t wait for the government to solve our problems – we have to do it ourselves. I started attending their events at the schools and in the community. Eventually, they asked if I’d like to be a member.

Perryman: What specifically about the Buffalo Soldiers piqued your interest?

LeFebvre: I’m a history student, and I’ve learned so much about the original Buffalo Soldiers and what they did from just after the Civil War until 1951, supposedly that I never learned in school. I had no idea there were Black cowboys. I didn’t know the Buffalo Soldiers had planned out and created the roads in our national parks and that one of them was the first African American superintendent of national parks.

I didn’t know they fought along the border and were the first border patrol. I didn’t know they helped the settlers cross the Great Plains and fought against the Indians and fought with Indians. I didn’t know they were the first sheriffs. I didn’t know the Lone Ranger was a Buffalo Soldier. The Buffalo Soldiers got the worst horses, crappy uniforms and lower pay than anybody else. However, they fought for this country to better themselves and their family’s lives.

And, even though when they came back from World War I and were being lynched down south, they continued to fight to make this place better than what it was to keep that promise, as it says in the Declaration of Independence, that we’re all created equal.

Perryman: WSPD is known, and even celebrated by some, for its conservative slant and perspective. How do you balance being a conservative voice while supporting initiatives that may challenge conservative policies?

LeFebvre: And that’s the thing, you should see my email and my Facebook page. Seriously, in one three-hour show, I can go from being a right-wing nut job to a left-wing radical because I don’t look at topics as a conservative.

We (WSPD) carry conservative shows because, number one, there aren’t any liberal shows out there. We carry shows that bring us the most listeners. In the morning, I do what I do, which is mostly local because it gets the most listeners for what I want to do in the morning.

Perryman: How can communities and individuals work together to bridge this divide in political perspectives, especially regarding race?

LeFebvre: If I had taken the attitude that I heard at home into high school, I wouldn’t have had any African American friends. However, I went into high school realizing that I was going to be surrounded by all these different people; I needed to take advantage of what they were offering, so I did. I had Black friends, Hispanic friends and some really good friends with whom I still keep in contact and live all over the country.

You can’t do this in groups, but if you can sit down with a guy, like Earl and I did, talking about what we had in common—the fact that we wanted to move the community forward, making where we live a better place—that stuff has to be accomplished one-on-one.

Perryman: In Toledo, the African American community faces higher unemployment rates than the general population. How can our leaders address those disparities?

LeFebvre: The current administration seems more in love with creating bike and multi-use paths, changing our city flag, and doing things like that. The neighborhoods are dying, but we have major development going up downtown.

I look at Dorr Street and see that stupid sidewalk they put in for the Solheim Cup from downtown all the way to Inverness. I can’t even imagine how much that costs, and the people who were coming in for the Solheim were not using that sidewalk.

Why aren’t we taking some of this money spent for the sidewalk, revitalizing what buildings can be fixable and refurbished, and saying, “Look, do you want to start a barbershop or other entrepreneurial effort here?” If we can give a tax break to Jeep and any other big company, why can’t we give it to this person? But no, instead, we do it for Stellantis, First Solar, Chrysler, and Jeep, and they don’t need it.

Perryman: Police – community relations and criminal justice, issues of police brutality, racial profiling and over-policing of minority neighborhoods. Do you want to talk about that?

LeFebvre: I would like to see more cops on the beat in the streets. I think that’s important. People in the neighborhood need to see a face they recognize, and the police need to recognize those residents. They need to know who the store owners are, who the teachers are when they come out of the classroom, and who the neighborhood kids are.

Not only that, but one of the things I learned a lot from Earl is that there has to be training. You can’t just take a new cop, like a new white cop, and throw him into a Black neighborhood unless that’s where he grew up, so he understands because he doesn’t get it. He doesn’t understand the attitude. He doesn’t understand the ingrained fear and distrust that African Americans have for the police. Cultural awareness and competency are essential for every neighborhood. You must know the people you’re working with.

Perryman: Let’s discuss disparities in healthcare and healthcare access, including reproductive rights.

LeFebvre: There are local events like The African American Male Wellness Walk, but until you convince people just how important it is to maintain their own health to the best of their ability, to demand healthcare and eat properly, stop smoking, and do the things that they can do, you can put all the hospitals out there you want, somebody’s going to have to pay for that healthcare somewhere along the line.

As far as reproductive rights go, I’m not a woman, so I don’t control any woman’s body. I can only control my own. If I don’t want my girlfriend or my wife to get pregnant, then I better take some precautions on how I approach her when it comes to sex.

Perryman: Did you read the Toledo Blade article based on a CNN report about the United States being last among wealthy nations in healthcare and access to healthcare? The article points out that the U.S. spends more than other countries on healthcare and gets the worst outcomes. I recommend reading Black Health by Dr. Keisha Ray, which might further educate you on that issue.

LeFebvre: Certainly.

Perryman: Lastly, let’s play a little word association.

LeFebvre: OK.

Perryman: Soul food?

LeFebvre: In Detroit, while working on 14th Street, every Saturday, the ladies in the neighborhood would come in and take our orders. Then, about an hour later or so, they’d come back with chitterlings, hog maws, pigs feet, collard greens, and all this stuff. I tried it once. I never acquired a taste for collard greens.

Perryman: Ethnic festivals?

LeFebvre: I love them and have learned much from them.

Perryman: Hip hop?

LeFebvre: I like hip-hop. “I like it when you call me Big Poppa.” I like Biggie. I go with everything from hip-hop to country, rock to rhythm and blues.

Perryman: Comedy?

LeFebvre: I love comedy. Queen Cookie was on with me just the other day. She just makes me laugh, and I love that it wasn’t until she was 63 that she said, “You know what? I’m going to try something…”, and it took her all the way to The Apollo Theatre in Harlem where she got a standing ovation and success all around the country.

Perryman: Wade Kapszukiewicz?

LeFebvre: I don’t like the mayor at all. I don’t think he’s done enough to get our police in line. The cops that sicced the dog on that guy, there should’ve been more consequence for that.

Perryman: Marcy Kaptur?

LeFebvre: We know a much better way to spend our money here than sending it to D.C. I don’t want anybody to be in office, whether it’s a Democrat or a Republican, for more than 20 years; that’s your term limit.

Perryman: Mike Bell?

LeFebvre: I like Mike Bell. I don’t see him often, but I’ve spent time talking to him after he retired, and I think the story is that he and his brother grew up being a part of the active community and swimming pools. He told me when he became fire chief, he wanted to do the rescue on the river stuff, and they looked at him and said, “Well, you know you gotta know how to swim?” Mike hadn’t told anybody that he spent every summer with his brother at the local swimming pool racing, so he said, “Oh really? Okay.” He’s just unassuming; just go out and get it done.

Perryman: Pete Gerken?

LeFebvre: I don’t like Pete Gerken at all. This dog warden thing, he’s got his name all over that. That’s a problem that had been brought to his attention sometime before.

Perryman: Kamala Harris?

LeFebvre: I like Kamala Harris. I just wish she would just be direct. I don’t care that you grew up middle-class, that your mom was a single mom, or that you worked at McDonald’s. I want to know from every politician what your plan specifically is. Like Trump said the other day, “Well, I’ve got ideas for a plan; a concept.” I don’t give a crap. Just tell me what you’re going to do, and then I will decide if I think that would work or not.

Perryman: Finally, Donald Trump?

LeFebvre: Not a fan. I didn’t vote for him last time, so I won’t again this time. It’s a temperament thing. If you’re an asshole, then you will not be in my circle of friends. I don’t treat people the way he treats people. It’s demeaning, it’s wrong, and I don’t want the face of my country, no matter what plans he might have in place. I don’t want the face of my country to be that ugly American that he is in so many cases.

His son Eric was in the studio with me in 2016, actually, and when we were done, he said, “So did I convince you to vote for my dad?” I said, “No, I’m sorry. I can’t vote for your father. I’m never going to vote for your dad. He’s just not the person I want to see as the President of the country I live in.”

He kind of looked at me like crap. “That’s not the answer I was expecting,” he said.

Contact Rev. Donald Perryman, PhD, at drdlperryman@centerofhopebaptist.org