By Fletcher Word

The Truth Editor

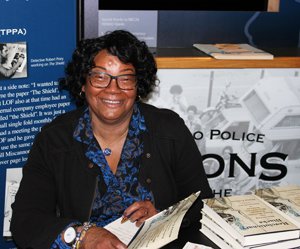

“If you are going to do history, you need to do history right,” said Shirley Green, PhD, historian and author of a new book, Revolutionary Blacks: Discovering the Frank Brothers, Freeborn Men of Color of Independence.

When Green was doing this particular history and doing it right, she discovered things about her own family’s history that delighted her, to be sure. Some degree of shock, however, was mixed in with that delight.

Green has had numerous accomplishments in her life. A former police officer, she was Toledo’s first ever female police lieutenant. She served as the City Safety Director during the Mayor Mike Bell administration. She has also earned a doctor of philosophy degree in history from Bowling Green State University and is currently an adjunct professor of history at the University of Toledo and Bowling Green State University

Now, above all, she is an historian and an author, someone who has drawn on her own family’s history and oral tradition to pen a work about the experiences of an African American family that was free well before the Revolutionary War.

The Frank brothers – William and Ben – are Green’s ancestors on her mother’s side. The brothers fought in the Revolutionary War, as Green was to discover, with a Rhode Island regiment. Eventually, Green’s mother wound up in Ohio, but she knew from the older generation that the family had roots, not only in Rhode Island, but also in Nova Scotia, Canada.

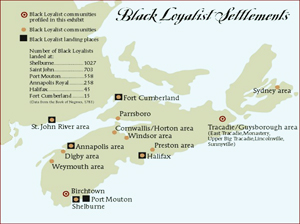

Green had always assumed, as had her mother and aunt, that her Nova Scotia ancestors had arrived in Canada after escaping from slavery. There are in fact a number of Canadian cities and towns where settlements for former enslaved people were established. Those fleeing slavery were prompted to cross the border especially after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 which enabled slave owners and bounty hunters to chase their slaves anywhere in the U.S. and imposed criminal penalties against those helping them.

Ontario towns such as London, Chatham, North Buxton, Windsor and Toronto established such settlements. So, it was natural to assume that the Black folks in Nova Scotia also ended up there as a result of the mid-19th century flight.

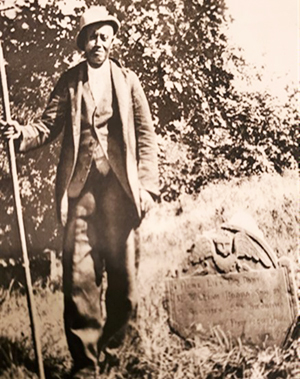

Green knew of her Nova Scotia connections primarily because of Thomas Henry Franklin, her great grandfather, himself a Nova Scotian. Franklin had the opportunity to pass along the tale of the family’s travels – in part, the role that two brothers, William and Ben Frank, played in those travels in the late 18th century – to a local Nova Scotia historian in the late 1920’s when Franklin was in his 70s.

Through oral tradition, however, Franklin passed down even more information to descendants about the route the family’s ancestors had taken to end up in Nova Scotia but, as Green would eventually learn, Franklin passed down considerably more to the male side of the line.

Green knew that Franklin’s son, her grandfather, left Nova Scotia in the early 1900s for New York looking for a better life, eventually serving in the Army during World War I and fathered two sons who served in WWII. His youngest daughter, Sarah, Green’s mother, attended Wilberforce College and settled in Ohio.

As Green writes: “The bigger story, passed down only through male members of the family, described how the first member of the Franklin family came to America from Africa by way of Haiti, an enslaved man who eventually gained his freedom. Two of his descendants – two freeborn brothers with the last name of Frank – fought together in the “Black Regiment” from Rhode Island of the Continental army during the American Revolution. It was a story about a manly struggle for liberty and acts of freedom. It was a wonderful story that pulsed with pride in the past”

However, as Green herself would discover, this “bigger story” was not the complete story. And the complete story, when she finally uncovered it, would be a complete surprise.

Green was in class working on her doctorate in 2011 at the University of Toledo taking a course on African American history when Professor Nikki M. Taylor mentioned that Black migration to Nova Scotia was a result of loyalty to the British during the Revolution not flight during the time of the Underground Railroad.

Green went back to her mother, who went back to her sister and finally to a brother, Green’s uncle, who told the story of two brothers who fought in the Continental Army. The mystery remained. How did part of the family end up in Nova Scotia … and when?

Green’s task, as she saw it, was to connect the two stories as she delved into her family background. She did that and more. She discovered how and why the family of the two Frank brothers ended up in both Rhode Island and Nove Scotia. She also managed to uncover ancestors that predated the Franklin brothers by almost a century.

First, Green delved into vital, census, marriage and military records from Rhode Island data; she later found settlement records in Nova Scotia. She confirmed that the Frank brothers, William and Ben, were free men well before the American Revolution.

Rufus Frank, a veteran of the French and Indian War, established a household in Rhode Island in the mid 1700s and was the father of William and Ben. William and Ben, carrying on the tradition, enlisted in the First Rhode Island Regiment of the Continental army. Green was able to detail quite extensively how the First Rhode Island Regiment, and the Frank brothers, spent the Revolutionary War.

The conditions were brutal in many ways. Underfed, poorly outfitted and not often paid, the regiment experienced a large number of desertions as soldiers left to return to their farms or to join the British side. The Rhode Island Regiment spent that brutal winter of 1777-78 in Valley Forge, the third and harshest of the eight winter encampments of the war. Of the 12,000 soldiers George Washington led into the encampment in December 1777, an estimated 1,700 to 2,000 died from disease, probably exacerbated by malnutrition.

“The compiled service records housed at the National Archives and the military records at the Rhode Island State Archives and Rhode Island Historical Society provided the first clues to solving the mystery of the Canadian Franklins’ lineage,” writes Green.

William Frank served honorably for a total of six years and after the war returned to Rhode Island. Ben Frank, on the other hand, served for only three years … then deserted.

Ben headed for British lines and after the war, left the United States, along with other British loyalists – soldiers and civilians, Black and white – and arrived in Nova Scotia.

Green’s discovery of the real story, “the uncomfortable part,” was not easily accepted by her family.

“They scrutinized my findings, questioning me and providing guidance to make sure I was now getting the ‘real’ story.”

The real story, while it may have been uncomfortable, turned out to be fascinating, much more fascinating than it would have been if there had only been one branch on the family tree.

Green’s work was far from complete with that discovery, however. Her additional research into Rhode Island documents took her further back in time and unveiled an ancestor of Rufus Frank known as Frank Nigro who, by 1694, “had established himself on Providence, the hometown of Rufus Frank.” Frank Nigro would gain his freedom a few years later and the racial identifier “Nigro” would be dropped. He became “a purchaser of land; was a landowner who leveraged his property for money …” among other documented events. This industriousness, writes Green, set the example for the Frank men who would follow him.

Using oral tradition, exhaustive documentary research and genealogical science (DNA), Green has compiled her family’s history that is both compellingly interesting and convincingly accurate. The two brothers’ – William and Ben Frank – divergent paths during the American Revolution and the Canadian side of the family’s re-entry to the States in the early 1900s – John William Franklin, Sr – present an almost unique tale for a Black family in this hemisphere. Only 10 percent of African American families can trace their roots to before the Civil War, according to data compiled by Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates (Finding Your Roots, season 1)

“In this book, I recount the lives of the Frank/Franklin families from the 1750s until the 1830s. I show how Frank men used their military service to assert their manhood, gain standing in their community, and help to create free African American and African Canadian communities,” writes Green in the book’s introduction.

Green has more history to delve into. Next up is a look at the story of Albert King, the first Black Toledo police officer in the late 19th century. Green will be working with the African American Police League to honor King by placing a marker at the tomb in Toledo where he and his wife, their three daughters, a sister in law and a “boarder” (whose identity is not quite certain yet) are buried.

In addition, she will be quite involved in the approaching ceremonies for America’s 250 anniversary in 2026 – the semiquincentennial. In the next few months she will be speaking to a group in the Hudson River Valley that is planning a series of activities.

Such events mean that in the future Green will undoubtedly be enlightening readers with so many more fascinating lessons from history.