By Rev. Donald L. Perryman, Ph.D.

The Truth Contributor

For the advancement of peace and unity, I shall pity the faults of my fellow man and praise his virtues, forgive his injuries and proclaim his favors, hide his stains and display his perfections, hoping that he will be likewise charitable toward my own shortcomings – Carter G. Woodson

Toledo has a long and storied history of individual ministers belonging to Black mainstream denominations involved in social activism.

Some religious leaders have engaged in community work with a “Burn baby, burn” activist approach emphasizing a strategy of bold criticism and protest against the system. Others, however, are “actionists” who navigate the system to empower their community itself rather than attack the system.

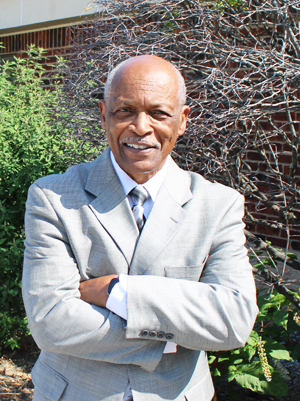

While both approaches have an important role in societal change, Rev. Dr. Otis Gordon has emphasized a pragmatic approach focusing on self-empowerment, self-sufficiency and maneuvering through the existing system to achieve community goals.

Known as a peacemaker rather than a hell-raiser, Gordon will deliver his final sermon on October 1 before retiring after a 20-year stint as the Warren A.M.E. church pastor. He will also be honored at a banquet on September 15.

During his 53-year pastoral career, Gordon has pastored churches in Massillon, Kent, Cleveland, and Warren, Ohio, before coming to Toledo. In his time in Toledo, Gordon forged peace, not by denying the presence of racism and injustice or by avoiding its systemic power, but by proactively and not reactively facing these structures head-on.

I spoke with Pastor Gordon to discuss his reflections on his effectual career in Toledo. Here is our conversation.

Perryman: Congratulations on your retirement. Let’s talk about Warren AME’s legacy and history.

Gordon: Warren was founded in 1847 due to the Underground Railroad, where Blacks who came here were en route to Canada. We began as a school to attract people who needed to further their education or learn the basics, and from there, they became a church. Warren was originally located on Summit Street. A marker right across from the Imagination Station today marks the place of the first church.

Perryman: What comes to mind when most people think about Warren?

Gordon: Historically, Warren was a place where many of the major meetings were held. For example, Sojourner Truth, the NAACP, met here. They had community meetings here at the turn of the century. Frederick Douglass also had some meetings here. Warren is known as a church like Third Baptist, one of the first churches here that Blacks populated in the city.

Perryman: Warren also carries a legacy of involvement in The Civil Rights Movement.

Gordon: Yes, and that’s one of the points of AME Methodism. We’ve argued that our founding was a result of injustice because it was a result of racism within St. George’s Church when Richard Allen, who was a free enslaved person, began to teach Sunday school, and his class grew larger than the white classes. They relegated the Blacks to stand on the outer side of the sanctuary during worship, and then put them in the balcony. The final point happened when the pastor called for an altar call, and African Americans who were in the church at the time had to come down from the balcony, and so they were the last ones at the altar. When the Blacks knelt at the altar, the usher, or the sexton, as they were called, began to pull them from the altar. Richard Allen, along with Absalom Jones, objected and said, “Please wait till prayer is over, and we will trouble you no more.” So, they got up and walked out, vowing never to return. That was the first Civil Rights protest, we believe, that occurred in the United States.

Perryman: The AME denomination has also been a big proponent of education and literacy, establishing numerous schools and colleges.

Gordon: Absolutely. Daniel Payne was a strong advocate for education and literacy because he believed that for African Americans to move forward, we needed to have an educational basis, and he felt it was essential to help educate Blacks. For that reason, we have several universities. Wilberforce, the oldest predominantly black school in the country, was founded by Bishop Daniel Payne and named after William Wilberforce, the great statesman and liberator from England,

Perryman: Talk about your calling and where it began.

Gordon: I am a product of St. Andrews AME Church in Youngstown, Ohio, which at the time was the largest African American church in the city. Interestingly enough, I was ordained an elder in the AME Church at the North Ohio Conference, convened at Warren AME in Toledo in October 1970. So, my ministry really began here in Toledo. At that time, I had no idea that I would ultimately become the pastor of Warren at the close of my career.

Perryman: How did you become active in social justice issues?

Gordon: Before coming to Toledo, my Bishop appointed me to pastor Grace AME Church in Warren, Ohio. I remained their pastor for 13 years, dealing with a congregation’s problems in the midst of decline, and the city was amid decline educationally, economically and racially. That’s where I learned to be involved in various justice issues.

I had been the presiding elder of a friend from Cleveland. He told me that when the Rodney King situation occurred, his mayor called and asked him for help because the mayor feared that they would have a race riot and asked if the African American church would help. My friend then reached out to a white Lutheran pastor, and both of them connected with a group of scholars from New England. They wrote this curriculum called Study Circles for Blacks and whites to sit down and discuss their differences and racial issues in a nonthreatening manner.

Perryman: What did you learn from that strategy?

Gordon: It just so happened that a couple of years after that, the mayor of Warren, Ohio called me and said they had a problem. Two black kids allegedly “broke into the Catholic rectory, beat up the priest, and stole money.” I said, “Yes, I saw that on the front page of the newspaper” He said, “Well, it didn’t happen that way. We know now that the priest lied; he faked the whole thing, and there’s going to be a race riot once that comes out. What can we do?”

I remembered the program called Study Circles. I said, “Mayor, we’ll bring all the African American preachers together, have a press conference and call for calm, and follow that with a unity prayer service. And, to put substance to it, we’ll begin the Study Circle process for Warren, Ohio because we need it anyway. That’s precisely what we did, and it turned out to be tremendous. Blacks and whites came together; they worked on racial harmony. We even had a unity prayer service, filling a music hall that held over 1,000 people. That was the high point I think of my time there and that we averted what was potentially a race riot because every summer before that I had to intervene.

There was one point where we, IMA, walked the streets to make sure there was no violence because of problems within the African American community. So that’s where I learned to become involved in the community and carry out what I thought was the mandate of the AME Church going back to Richard Allen.

Perryman: Your leadership style seems to be that of a peacemaker rather than a disrupter or protester like the Apostle Paul, whom many people could call an accommodationist. Have you ever been criticized for being too accommodating?

Gordon: Absolutely.

Perryman: How do you respond?

Gordon: Well, Otis Gordon is just exactly as you said; I am the peacemaker. I want to find reconciliation. I want to see my people advance. I was working with the NAACP. Frank Hearns, the president of the NAACP, joined my church because he was so impressed with the changes I was helping to bring back through the city.

Remember the situation with the priest and the unity rally? Well, Hearns was opposed to it. Still, I convinced the majority of the Black preachers to support this, that it would be in our best interest. By the way, because of what I was able to do, we secured finances for a community center called ACOP, which still stands today serving that community, built by community funds.

But anyway, the newspaper interviewed me, and they also interviewed Frank Hearns. On one side of the middle of the article on the front page was this packed auditorium with this white lady with her hands raised praising God, and you looked into this picture, you’d see Blacks and whites worshiping. And then on one side was my picture with my viewpoints on why we needed to have reconciliation.

And then on the other side was Frank Hearns’ picture, why he was saying that this is no time for prayer. It seems you had two Black preachers disputing one another and this white lady praising God with other Blacks in the middle. I thought it was just the wrong picture. It’s as though they were using us to highlight our differences. Now bear in mind, Frank and I were friends, we just disagreed on how to achieve racial harmony, and after that, we worked together on many other things, but that’s an excellent example of where my personality, which is a person who seeks reconciliation, created some problems for me.

Perryman: How did that style of reconciliation develop? Where can you point to in your history?

Gordon: I think it goes back to my childhood. I was always a reconciler, and I always sought peace. Still, I attribute it to my background in English literature and philosophy. Those who reasoned well could always solve problems and bring about change. Shakespeare, specifically, his thing was everybody has this tragic flaw, and this is what Jesus taught as well, you cannot change circumstances until you change hearts, and that’s what I was always about.

It actually goes back to the Civil Rights era. I don’t want to tell you this, but I felt I was more conservative than most of my colleagues at the time. I was a youngster when Martin Luther King led the Movement. I thought he was a great orator but wondered whether we were moving too fast. Now, of course, I regret thinking that and even saying it. But in hindsight, I have to admit that I was totally wrong, and I would’ve handled it differently if I had known that. Now, I feel the exact opposite. In fact, I’m more militant now than I ever was. So, my style goes back to my early years in the ’60s, and it’s just my personality.

Perryman: Provide some examples of how you’re more militant now.

Gordon: Now, I don’t see any solution other than for us, Blacks, to come together and to work towards building ourselves up. Even though we’re moving two steps forward, we’re constantly taking one step backward, and it’s just a challenging situation. My philosophy is that unless we speak up for ourselves, no one else will. We need to be more determined to bring about change than ever before.

It just seems that racism has always been with us from the beginning of time, and it’ll always be there. I used to think that reasonable minds could always agree, but I’m not so sure now.

Perryman: Can you share any memorable moments from serving Warren here in Toledo that you will cherish as you retire?

Gordon: There were a lot of memorable moments. The first one was my first Sunday here. I always thought the church was such a beautiful sanctuary and a beautiful setting. There were also memorable moments of losing. I’ve funeralized hundreds of people since I’ve been here and gotten to know them. They impacted my life, and I remember each of them and so many of those funerals I will never forget.

I’ll never forget we’ve successfully hosted several annual conferences here; that was a memorable moment. Another special moment was when we built the senior center at the other end of the parking lot. This turned out to be a loving congregation. Still, I have experienced great loss, pain, and triumph in this season of my ministry right here at Warren. Of course, this is where I lost my wife of 42 years and was able to remarry, so yes, very significant loss and great meaningful joy.

Perryman: In what ways do you plan to continue serving the community, even in retirement?

Gordon: I hope my colleagues invite me to serve as a guest preacher in their congregations. I do want to preach as often as I am asked. Obviously, I will not preach at Warren, but I want to serve the community on various boards. I will continue serving wherever I am asked for the betterment of the community. I still believe in reconciliation and bringing blacks and whites together because we must work together. I firmly believe that Blacks can’t change this condition by themselves. We need everybody, including the government, to participate in this process of improving our community. We are at fault to some degree, but so is the system, and unless we address systemic racism, nothing will change.

Perryman: What message would you like to leave with your congregation and the broader community as you retire?

Gordon: You’ve asked me a question I don’t have an answer for right now. I’ve been searching for an answer to that question because I asked myself what I will say to the congregation on my last sermon, the first Sunday in October.

I concluded that there’s nothing I can say that I haven’t already said, but since you put the question to me, the legacy I would like to leave with Warren AME Church is to continue a Christ-centered ministry that reflects Christ to families, to young people, and to help young people believe in themselves that they can experience upward mobility.

Contact Rev. Donald Perryman, PhD, at drdlperryman@enterofhopebaptist.org