By Rev. Donald L. Perryman, Ph.D.

The Truth Contributor

A ‘formed’ personality operates like a straitjacket. We stiffen over time into our repetitive, ‘regular’ selves. Unless and until we make changes, we are obliged to operate from that stiff place without much room to move or breathe. Likewise, [conforming] straightjackets us. – Eric Maisel

The first thing I thought of upon hearing of Tina Turner’s death last week was the courtroom scene in “What’s Love Got to Do With It.”

“It means you’ll walk out of here with absolutely nothing.”

Angela Bassett – Tina Turner replies: “Except my name! I’ll give up all that other stuff, but only if I get to keep my name. I worked too hard for it. Your Honor.”

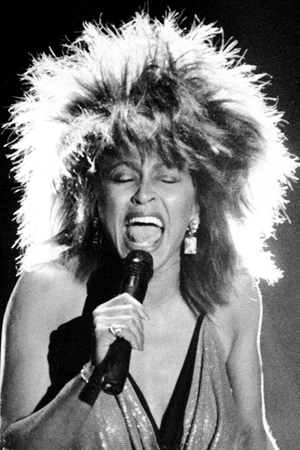

So, yes, Turner’s talent, dynamic energy, resilience, strength, and ability to overcome countless challenges of adversity to rise from ashes like the legendary phoenix made her an icon and the soulful queen of rock’ n’ roll.

However, Turner merely wanted to be herself in a world hell-bent on power and domination.

As a child, she got kicked out of the Black Church, “needing to experiment and take risks as part of individuality, and feeling thwarted and frustrated by the conventional universe into which she always seemed to find herself plopped.”

Yet, the one dynamic we always find in heroes is the fight to keep individuality rather than conform to societal pressures or that of others.

I spoke with Staci Perryman-Clark, Ph.D., about Tina Turner’s “Wild Ride of Individuality.” Perryman-Clark serves as Director, Institute for Intercultural and Anthropological Studies at Western Michigan University where she is Professor of English and African American Studies. She is also my daughter.

Here is our conversation.

Perryman: When I heard of Tina Turner’s passing, I almost immediately thought about how much you fantasized as a child about Tina Turner. Can you talk about that?

Clark: Yes, I did. I used to put on Mama’s wigs and high heel shoes, and I would put on a short skirt and probably with my favorite pajama top still on, and I would walk down the stairs because I thought my legs were pretty like hers. I wanted to be her.

Perryman: I’m sure of the importance of make-believe play for children, but I’m exploring your mind and thought process. How old were you, and what was going through your mind?

Clark: I Had to be about two or three years old. I liked the soulful rock ‘n’ roll, and I loved the video ‘What’s Love Got to Do With It’; that’s how I got the image of her. That was the first image I had seen of her to emulate.

Perryman: So, let’s talk about a two or three-year-old’s mind and imagination, which we know for Black children, play can be transformative. I remember you’d be running around trying to sing. ‘We Don’t Need Another Hero’ in Turner’s husky voice.

Clark: I remember watching the video and asking Grandma Freddie, raised in a generation in the South, taught to conform to the strict conventions of Jim Crow segregation, “Who is that?” and she said, “Some old wild woman.”

But, when she called her a wild woman, that’s exactly who I wanted to be; I wanted to be ‘Wild Woman.’ And if you think about it now, a performer, somebody with no boundaries, and someone that can just be free, that’s what I wanted to be. And I thought her legs were pretty, and mine were pretty, so I thought that would be a good match.

Perryman: What did ‘wild’ or ‘free’ mean to you as a two or three-year-old?

Clark: At that time, it meant that you could do what you wanted. If I wanted to be wild and jump off dressers to the bed or jump around, I could do it, and I wouldn’t have to be told to stop or to sit down. If I wanted to wander in the woods behind the house to explore, I could do it. I didn’t have just to sit still.

Clark: At that time, it meant that you could do what you wanted. If I wanted to be wild and jump off dressers to the bed or jump around, I could do it, and I wouldn’t have to be told to stop or to sit down. If I wanted to wander in the woods behind the house to explore, I could do it. I didn’t have just to sit still.

Perryman: I see. It provided a space to just be – to make mistakes, be silly, or be messy. Or even just explore. That space is sometimes not provided for Black children. But children’s play also plays a role in shaping their future adult identities. How do you think the dramatic play around Ms. Turner affects you today?

Clark: I still am a performer. I still want to be free. But, still, I don’t like boundaries. I still like to do whatever I want, for sure. So please don’t give me limits. And the eccentric hair, that wig also is very telling.

Perryman: You’re a creative writing and English professor. So, has your early dramatic play around Ms. Turner helped to boost your creativity or enhanced your communication skills?

Clark: Let me start with grown-up first because I was looking at some edits from my manuscript from writing with some folks. The person editing it told me to watch my run-on sentences. So, I’m like, ‘now I’m an English professor, I know what a run-on sentence is,’ and I’m like, ‘none of these are run-on sentences; they’re just an appositive. So, you have a comma, the person who was the x,y,z, that’s not a run-on sentence; you don’t have punctuation in run-on sentences.’

And for me, it was like that’s my writing style. There might be a more concise way to say it, but I don’t want to be told that there are grammatical errors. I want to write how I write. I know the rules, and I’m like, ‘None of these are run-on sentences, and you don’t even know their definition. Some have multiple clauses, but that doesn’t mean it’s a run-on sentence. When you add a relative pronoun to something with commas, it’s typically what they call an appositive, not a run-on sentence.’ An appositive is correct, so I’m sick of people telling me the rules and don’t know them, so I want to make my own rules.

Perryman: Is it possible that you become oppositional or rebellious in “doing your thing?” We still must have rules.

Clark: Obviously, there are limits; you can’t break the law, but any prescription of norms I’m very skeptical about because that’s somebody in a position of authority telling you what they should be, and that’s based on their experiences, not mine.

Imagination should liberate you and liberate others. If it doesn’t, then that’s when things are bad. It should liberate others to do something good, a collective good, not give people the freedom to harm others or use violence. That’s not liberation.

Perryman: Yes, it’s domination and imposing someone else’s narrow preferences or perspectives upon you, which is the opposite of freedom.

Clark: Right. This way, you stay out of my way and stop stifling my creativity, and I’ll leave you alone. Then, we can coexist.

Perryman: So, back to Tina. When you heard the news of her passing, how did that affect you?

Clark: I went immediately back to that little girl who, the first time I saw on TV, my grandma said, “Wild Woman.” I wanted to be her. I don’t know; I still do.

Clark: I went immediately back to that little girl who, the first time I saw on TV, my grandma said, “Wild Woman.” I wanted to be her. I don’t know; I still do.

She did a lot of things on her own terms, especially when she got away from Ike, and that’s something that resonates. Also, there’s something about the little girl imagining herself on a stage performing like her, being eccentric, and being okay. I don’t know; I still feel like I want to be her.

Perryman: You felt she was eccentric?

Clark: I did, in some ways, especially her videos and all the wigs. You’ve got to be eccentric. Even just the soul singing style with the kind of rock edge, she had an edginess, and I liked that too. But I wanted to be her; I just wanted to be free. I want to be free.

Perryman: I hear you saying, possibly, that women and people of color need “safe environments to carve out radical spaces for themselves due to fears, anxieties, and biases associated with living in an anti-black society.” On her discography, any favorite songs?

Clark: So ‘Proud Mary’ is always one of my favorite songs, but also the one I think she did in ’93, ‘I Don’t Wanna Cry No More,’ so ‘I Don’t Wanna Fight’ is what it was called.

Perryman: How does that touch you?

Clark: It is a way for me to disengage from conflict. It doesn’t matter who’s wrong or right sometimes. The older I get, the more I become attuned to figuring out this is not the hill I want to die on and just letting it go, especially at work. In some ways, I want to return to not taking myself too seriously, especially at work. Some of these things aren’t worth it, so I’m involved in less conflict.

Perryman: What will the world miss with Ms. Turner gone, and what will they remember?

Clark: We will remember her taking back her womanhood and fleeing an abusive domestic violence situation. I think what we can take from that is very feminist-centric. I don’t think she gets the credit that perhaps she should. Still, there’s something about her reclaiming her life, being an icon, and even moving to Switzerland, doing things on her own terms, and making those decisions for herself. I think that’s something that should resonate with all women. She had to start over in her late 40s, and that kind of triumph, I think, is something the world should remember.

Perryman: I asked your mother what she remembers most about you and your Tina Turner fantasy. She recalls that you would get up as a toddler and attempt to dress yourself. Your mom would dress you like a little girl. Before noon you’d removed all your clothes and replaced them with high heels and an old skirt, writing on your leg, trying to make tattoos.

“Do you think I wanted to see her day in and day out walking around the house in a ratty wig, a pink pajama top, a skirt, and heels? And people would come over and see her like that,” she says. Then, finally, your Aunt Jean asked, “Aren’t you afraid she will fall down the steps?” Your mom replied, “She goes up and down those steps all day long. She’s fine. And even now, Staci marches to the beat of her own drum. So, we allowed her to do that. I didn’t care if people thought she was strange. I just was not interested in changing her. I said no, you don’t dare change her, so let her be. That’s who God created her to be. She’s just different.”

We didn’t know a lot about successful parenting. We just attempted to allow you to celebrate your beauty, brilliance, creativity, and individuality. That decision has been transformative as you have channeled them into your writing and teaching.

So, I think we both learned that it is necessary for all children – safe, liberatory spaces for them to play.

Contact Rev. Donald Perryman, PhD, at drdlperryman@enterofhopebaptist.org