Harold Brown, a Catawba Island resident and frequent visitor to Toledo, passed away last week at the age of 98. The following is an article The Truth published in 2007 about this airman and educator.

November 14, 2007

Harold Brown: There … By Request

By Fletcher Word

The Truth Editor

After a long, fitful night, 2nd Lt. Harold Brown was once again taken from his cell and brought before his Oxford-educated interrogator. Name, rank and serial number was all he had offered on the previous day but … name, rank and serial number had proven to be unsatisfactory responses to the German major’s inquiries at the Nuremberg interrogation center.

The major, in perfect English, assured the 20-year-old fighter pilot who had been shot down on his 30th mission that if more complete answers were not forthcoming, he would be turned over to the German civilians.

German civilians were particularly hard on downed Allied pilots who, after all, had been responsible for such extensive damage to their country. And Brown had just recently seen the toll that civilian justice had exacted on one of his fellow Red Tail pilot colleagues.

“He was a mess,” recalled Brown of his comrade in arms. Fortunately, the following morning somehow produced a change in attitude on the part of the German. He greeted Brown and offered him a large, sweet orange – a gift Brown accepted without hesitation. “He then told me I didn’t know anything about my outfit that he didn’t already know,” said Brown.

As if to prove that his statements were not empty boasts, the German took the young lieutenant into his office and produced books on each of the four squadrons that comprised the by the known 332 Fighter Group – the Tuskegee Airmen.

Well known, it appeared not only to the American bomber pilots who were requesting the “red tails” with increasing urgency as the strategic air campaign raged on but also to the Germans who had taken note of the black pilots’ exploits – exploits that included never losing any of the bombers they escorted to enemy aircraft fire.

Well known, it appeared not only to the American bomber pilots who were requesting the “red tails” with increasing urgency as the strategic air campaign raged on but also to the Germans who had taken note of the black pilots’ exploits – exploits that included never losing any of the bombers they escorted to enemy aircraft fire.

The German major had concluded that Brown was in the 99th Squadron and that, given his age, he must have graduated the previous year in class 44C, 44D, 44E or 44F. Brown, a graduate of class 44E and member of the 99th, munched on his sweet orange in silence wondering at that time how the Germans had obtained such information.

“They had so much,” said Brown recently as he recounted a few war stories for a visitor at his home on Catawba Island. “I heard later that the sources of so much information were the newspapers of every major city in the United States.” The orange was not the only thing the major had to offer his prisoner.

“’Let me give you some advice’ he told me,” recalled Brown. “’This war is going to end in the next three to four months. You are going to be transferred to [a prisoner of war camp]. Keep your nose clean … don’t try to escape or give a guard any reason to shoot you.’”

The major, who also told Brown that his own goal was to try to get to the United States after the war, was nothing if not unerringly accurate in his assessment of the status of the war. Brown, along with about 10,000 other Allied prisoners, was forced marched to his new home at Stalag VII-A in Moosberg and remained there until May 3 or 4 when General George Patton and his 3rd Army arrived to liberate the prisoners of war.

Brown has no idea what happened to the German officer who extended more courtesies to him than just about any white American officer, or enlisted man for that fact, would during those days when black soldiers, sailors and airmen knew nothing but segregation and constant derision of the notion that they were matches for their white counterparts on the battlefields of World War II.

But the German fighter pilots knew about the “red tails” as did the American bomber pilots.

The American public would not know about the unit until 1995 when Bob Williams, Brown’s 44E classmate, would finally get his screenplay produced and his story told about the Tuskegee Airmen in an HBO movie starring Laurence Fishburne. Fifty years after he was shot down in Germany, Brown and his fellow heroes finally emerged from behind the cloak of secrecy in which they had been shrouded.

In December 1998, President Bill Clinton presented General Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., the commanding officer of the 332nd Fighter Group and the first African-American general of the Air Force, with a fourth star and celebrated the Tuskegee Airmen’s collective heroism.

In March of this year, President George W. Bush presented the pilots the Congressional Medal of Honor. “I have a strong interest in World War II airmen,” said Bush during that ceremony on March 29, 2007. “I was raised by one. He flew with a group of brave young men who endured difficult times in the defense of our country. Yet for all they sacrificed and all they lost, in a way, they were very fortunate, because they never had the burden of having their every mission, their every success, their every failure viewed through the color of their skin. Nobody told them they were a credit to their race. Nobody refused to return their salutes. Nobody expected them to bear the daily humiliations while wearing the uniform of their country.”

In March of this year, President George W. Bush presented the pilots the Congressional Medal of Honor. “I have a strong interest in World War II airmen,” said Bush during that ceremony on March 29, 2007. “I was raised by one. He flew with a group of brave young men who endured difficult times in the defense of our country. Yet for all they sacrificed and all they lost, in a way, they were very fortunate, because they never had the burden of having their every mission, their every success, their every failure viewed through the color of their skin. Nobody told them they were a credit to their race. Nobody refused to return their salutes. Nobody expected them to bear the daily humiliations while wearing the uniform of their country.”

Bush praised the Tuskegee Airmen for doing so much for a nation that had done so little for them and he told the story of one such pilot who had sacrificed virtually all of his worldly possessions in order to get to the training site to become a pilot. It’s a story with which Brown was thoroughly familiar.

Brown’s own love of flying was instilled at an early age when he dreamed of becoming a pilot while building model airplanes and reading books such as “The Life of a Flying Cadet,” a book Brown read so often he said later he could probably recite it from memory. A Minneapolis native, Brown volunteered in 1942, at the tender age of 17, for the Army Air Corps in order to become an airman. He was still in high school at the time.

He passed the written test easily, but flunked the physical. “I weighed 128 and one quarter pounds,” said Brown. “You needed to weigh 128 and a half pounds. I couldn’t believe they would reject me over a quarter pound.” They did. But the examiner did clue Brown in on how to pass the physical when he would be permitted to retake it in a week’s time.

“He asked me if I liked chocolate malteds, which of course I did,” said Brown. “He told me ‘on Wednesday, start early with a chocolate malted in the morning and one in the evening and put a raw egg in both of them.’” Brown did as he was advised and on the following week, he had ballooned up to 128 and three quarters pound, safely passing the physical by a quarter pound.

He would leave for Biloxi, MS in December 1942 to start his flying lessons, graduating in 1944 when he went overseas to Italy to begin flying his 30 missions. After the war, Brown reenlisted in what would become the Air Force. He remained in the military for 23 years. He earned a bachelor’s of science degree in math from Ohio University and his master’s and doctoral degrees from The Ohio State University.

He would leave for Biloxi, MS in December 1942 to start his flying lessons, graduating in 1944 when he went overseas to Italy to begin flying his 30 missions. After the war, Brown reenlisted in what would become the Air Force. He remained in the military for 23 years. He earned a bachelor’s of science degree in math from Ohio University and his master’s and doctoral degrees from The Ohio State University.

Brown joined Columbus State Community College as the vice president for academic affairs in the mid 1960’s when the two-year institution had 67 students and was located in a basement. He retired about 20 years ago having witnessed the school become the third largest community college in Ohio. Today CSCC has over 24,000 students.

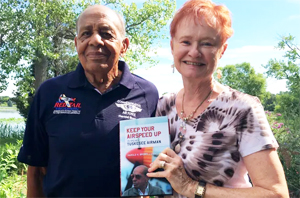

Retirement doesn’t exactly describe Brown’s current status. He formed a consulting company and the curriculum specialist stays on the road these days visiting two-year institutions around Ohio. And he stays in touch, of course, with the rest of the surviving members of the Tuskegee Airmen.

In his home on Catawba Island, as he spoke of the war days and the exploits of the pilots, Brown pulled out a miniature replica of a Mustang P-51 in which the Tuskegee Airmen flew so many sorties. The model has the familiar “red tail” that the black pilots painted on in order to identify their group.

Near the door of the model plane is a replica of a bit of writing that then-Captain Davis painted on his own plane and that message is a reference to the fact that white bomber pilots kept insisting more and more that the red tails escort them on their particular missions as the war went on.

It’s also a reference to the fact that their nation, however reluctantly, had called upon them for their assistance.

The two-word message describes ultimately just why the Tuskegee Airmen were in that place at that time. They were there … “by request.”