c.2020, The University of North Carolina Press

$34.95 / higher in Canada

353 pages

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

The Truth Contributor

Life, if you think about it, is somewhat like a necklace.

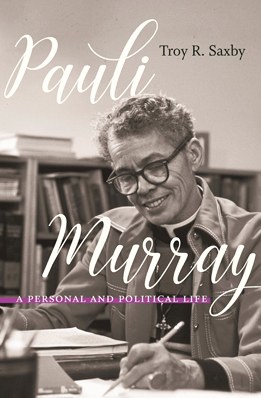

Imagine the first bead is birth, starting off a chain. This bead represents your fifth birthday, here’s your tenth, graduation, your first job, your first home, your firstborn. Some beads are larger but the smaller ones are not unimportant. And so it goes, but when building that metaphoric chain, as in the new book Pauli Murray: A Personal and Political Life by Troy R. Saxby, be aware of the links.

Almost from the day she was born, Annie Pauline Murray was challenged.

When she was three years old, her pregnant mother died, leaving six children to a husband who was abusive and mentally ill. Shortly afterward, Murray’s father entered a “psychiatric facility,” where he died when Murray was 12; between those losses, Murray was taken in and raised by an aunt in a poverty-affected but “respectable middle-class” household that contained more mental illness.

Though many of Murray’s Black family members “passed” as white, her closest guardians “gloried in the achievements of African Americans.” Young Murray had a “rebellious streak,” but she embraced the education her elders demanded, and was driven to excel: at college, many officials doubted that she could do the work required to succeed, and they told her so – but that “streak” made her more determined, which helped her achieve several college degrees, including one in law. Her accomplishments were many: Murray was an early feminist, she worked tirelessly and ingeniously for the Civil Rights Movement and for social justice, but her successes didn’t buoy her.

Always a “tomboy,” Murray had love affairs with women through the years, but furtively, given the times and lack of tolerance for homosexuality. She seemed to embrace that love, but it also seemed to bother her: she asked doctors if there was something inside her that was more male than female, as if she were a “hermaphrodite.” This, perhaps, as well as racism, self-pressure to succeed, confrontationalism, and mental illness that plagued her family caused “almost annual breakdowns…”

While it starts out fascinating, with descriptions of the era in which Murray’s forebears lived and of her earliest years, Pauli Murray becomes too much, too quickly. It’s comprehensive, that’s a fact – author Troy R. Saxby seemed to leave no stone unturned – but infinitesimal details of Murray’s life are abundant here, every argument, movement, and visit, and that can be overwhelming.

And yet, there’s so much to glean from this book, so many milestones Saxby says Murray set, that you almost can’t stop reading despite watching the discomfort, obvious pain, and inner struggle she endured. Through letters and articles she wrote, readers get to know Murray as she perceived herself; those personal peeks are engrossing, especially given the legacy she left when she died almost exactly 35 years ago.

If you have the patience, or the ability to skim when overpowered with minutiae, Pauli Murray is ultimately, absolutely worthwhile. Especially now, any reader who wants to know more about social justice pioneers should get a bead on it.