c.2024, Smithsonian Books

$39.95

240 pages

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

The Truth Contributor

Ever since you learned how it happened, you couldn’t get it out of your mind.

People, packed like pencils in a box, tightly next to each other, one by one by one, tier after tier. They couldn’t sit up, couldn’t roll over or scratch an itch or keep themselves clean on a ship that took them from one terrible thing to another. And in the new book In Slavery’s Wake, essays by various contributors, you’ll see what trailed in waves behind those vessels.

You don’t need to be told about the horrors of slavery. You’ve grown up knowing about it, reading about it, thinking about everything that’s happened because of it in the past four hundred years. And so have others: in 2014, a committee made of “key staff from several world museums” gathered to discuss “telling the story of racial slavery and colonialism as a world system…” so that together, they could implement a “ten-year road map to expand… our practices of truth telling…”

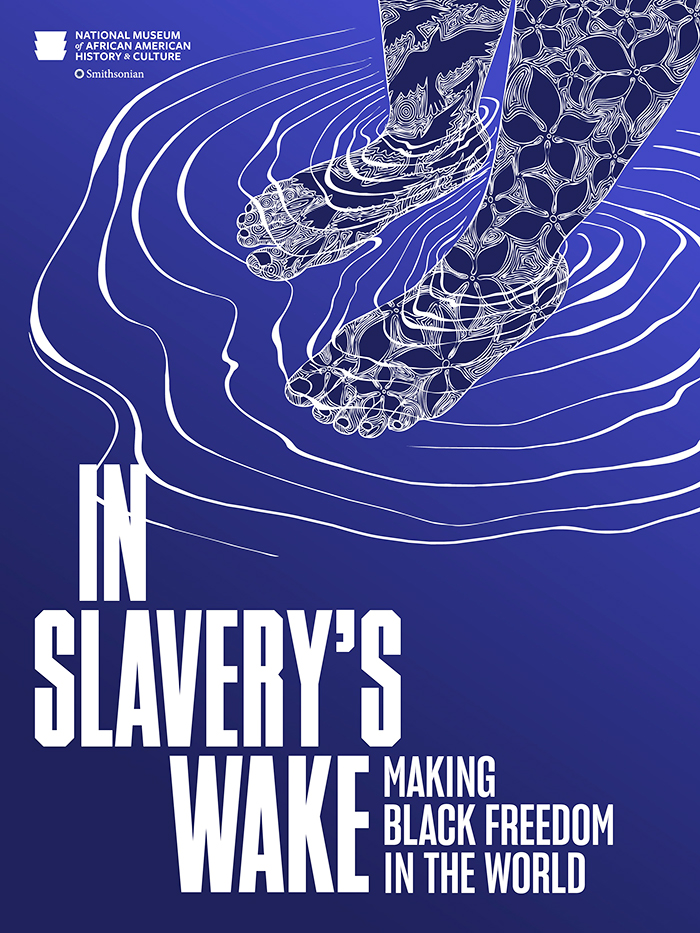

Here, the effects of slavery are compared to the waves left by a moving ship, a wake the story of which some have tried over time to diminish.

It’s a tale filled with irony: says one contributor, early American Colonists held enslaved people but believed that King George had “unjustly enslaved” the colonists.

It’s the story of a British company that crafted shackles and cuffs and that still sells handcuffs “used worldwide by police and militaries” today.

It’s a tale of heroes: the Maroons, who created communities in unwanted swampland, and welcomed escaped slaves into their midst; Sarah Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus”; Marème Diarra, who walked 200 miles from Sudan to Senegal with her children to escape slavery; enslaved farmers and horticulturists; and everyday people who still talk about slavery and what the institution left behind.

Today, discussions about cooperation and diversity remain essential.

Says one essayist, “… embracing a view of history with a more expansive definition of archives in all their forms must be fostered in all societies.”

Unless you’ve been completely unaware and haven’t been paying attention for the past 150 years, a great deal of what you’ll read inside In Slavery’s Wake is information you already knew and images you’ve already seen.

Look again, though, because this comprehensive book isn’t just about America and its history. It’s about slavery, worldwide, yesterday and today.

Casual readers – non-historians especially – will, in fact, be surprised to learn, then, about slavery on other continents, how Africans left their legacies in places far from home, and how the “wake” they left changed the worlds of agriculture, music, and culture. Tales of individual people round out the narrative, in legends that melt into the stories of others and present new heroes, activists, resisters, allies, and tales that are inspirational and thrilling.

This book is sometimes a difficult read, and is probably best consumed in small bites that can be considered with great care to fully appreciate. Start In Slavery’s Wake, though, and you won’t be able to get it out of your mind.